Cannabigerol (CBG): A Minor Cannabinoid With A Major Impact

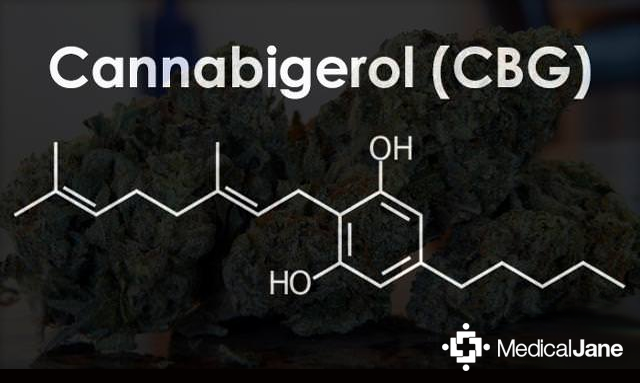

What Is Cannabigerol (CBG)?

When considering the medicine that best suits you, it’s helpful to know the science behind a strain’s cannabinoid profile. The prevalence of lab testing is a great tool and has rapidly become the industry standard. Teams of chemists at locations like SC Labs in California and Sunrise Analytical in Oregon allow patients to see the breakdown of cannabinoids in their medicine, to practically an exact percentage.

This trend has lead to an increased interest in the “minor” cannabinoids. Tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) was the focus of breeders for decades until the many medicinal benefits of cannabidiol (CBD) started being published. Discoveries like these spurred an interest in cannabigerol (CBG) and phytocannabinoids (cannabinoids found in plants) as a whole.

Cannabigerolic Acid (CBGA) Is The Primary Cannabinoid

The ability to produce cannabigerolic acid (CBGA) is what makes the cannabis plant unique.

It is the precursor to the three major branches of cannabinoids: tetrahydrocannabinolic acid (THCA), cannabidiolic acid (CBDA), and cannabichromenic acid (CBCA). The plant has natural enzymes, called synthases, that break the CBGA down and mold it toward the desired branch. The cannabis plant’s synthases (THC-synthase, CBD-synthase, CBC-synthase) are named for the cannabinoid they help create.

It is the precursor to the three major branches of cannabinoids: tetrahydrocannabinolic acid (THCA), cannabidiolic acid (CBDA), and cannabichromenic acid (CBCA). The plant has natural enzymes, called synthases, that break the CBGA down and mold it toward the desired branch. The cannabis plant’s synthases (THC-synthase, CBD-synthase, CBC-synthase) are named for the cannabinoid they help create.

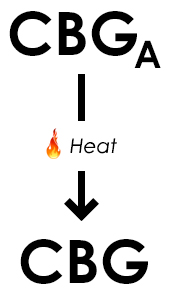

When any of the cannabinoid acids are exposed to heat, or prolonged UV light, they lose a molecule of carbon dioxide (CO2). At this point, they are considered to be in the neutral form (CBG, THC, CBD, CBC, and so on). In most medicinal strains, CBGA is immediately converted to another cannabinoid and is not typically found in high concentrations. However, if a strain is high in CBGA, then ingesting it by smoking would cause it to change to cannabigerol (CBG).

While most strains of cannabis are less than 10% CBG, industrial hemp strains test much higher. They have been tested as high as 94% CBG with as low as 0.001% THC.

Testing of industrial hemp has found much higher levels of cannabigerol (CBG) than most strains of cannabis. Further studies have shown that this phenomenon may be due to a recessive gene. This gene is believed to be responsible for keeping the plant from producing one of the cannabinoid synthases (what converts CBGA to one of the major branches).

That being said, breeders are able to manipulate a plant’s cannabinoid profile by adjusting the amount of each synthase it naturally produces. If a breeder wants to focus on a specific cannabinoid they are able to do so by cross-breeding two plants that are genetically predisposed to make a lot of it. In the case of CBG, the breeder would instead focus on plants with the recessive gene that inhibits the ability of the cannabinoid synthase.

In fact, Odie Deisel is one of the new head breeders at TGA genetics Subcool Seeds and he has helped create a strain with high levels of cannabigerol (CBG). According to the TGA website, Mickey Kush is a Sativa-dominant strain resulting from Sweet Irish Kush and Jack The Ripper. Not only does the Mickey Kush strain test at 28.6% tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), but the website boasts about its high CBG content as well.

The Effects of Cannabigerol (CBG)

The research surrounding this specific cannabinoid (and its effects) are somewhat limited. Restrictions on the testing of cannabis make it difficult to find volumes of quality research about cannabigerol (CBG).

Cannabigerol (CBG) seems to work with the other cannabinoids (such as THC and CBD) to provide overall synergy, as well as balance.

That being said, it has been classified as an antagonist of the CB1-receptor, which affects the central nervous system. Because of this, CBG is believed to partially counteract the paranoid, “heady” high typically associated with tetrahydrocannabinol (THC). Cannabigerol (CBG) has also been determined to affect the CB2-receptor, which influences the body more. However, researchers aren’t sure if CBG promotes or inhibits CB2-receptor activity yet.

Another effect cannabigerol (CBG) has on the brain is that it inhibits the uptake of GABA, a brain chemical that determines how much stimulation a neuron needs to cause a reaction. When GABA is inhibited it can decrease anxiety and muscle tension similar to the effects of cannabidiol (CBD).

An Italian study published in the May 2013 edition of Biological Psychology suggests that cannabigerol (CBG) has strong anti-inflammatory properties and may benefit patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). It is also useful in the treatment of glaucoma, as CBG can increase the fluid drainage from the eye and reduce the amount of pressure. Further, cannabigerol (CBG) has anti-depressant qualities and may inhibit tumor growth.

Cannabigerol (CBG) Deserves More Attention

Not only is cannabigerolic acid (CBGA) the first stage in the development of cannabinoids, but it has been found to have benefits of its own when smoked. It becomes cannabigerol (CBG) as a result of a CO2 molecule escaping the compound in response to heat (when you spark it).

Because of its newly discovered uses, breeders like Odie Diesel have paid more attention to CBG in their strains and patients should follow suit. Medicinal strains that are also high in cannabigerol (CBG) are likely to have a much more balanced effect. The CBG seems to help your brain find a happy medium amongst the rest of the cannabinoids, causing a feeling of synergy.

Citations & References

There are 3 references in this article. Click here to view them all.

- Meijer, E. P. M. De, and K. M. Hammond. “The inheritance of chemical phenotype in Cannabis sativa L. (II): Cannabigerol predominant plants.” Euphytica, vol. 145, no. 1-2, 2005, pp. 189–198., doi:10.1007/s10681-005-1164-8.

- Borrelli, Francesca, et al. “Beneficial effect of the non-Psychotropic plant cannabinoid cannabigerol on experimental inflammatory bowel disease.” Biochemical Pharmacology, vol. 85, no. 9, 2013, pp. 1306–1316., doi:10.1016/j.bcp.2013.01.017.

- Brenda K. Colasanti. Journal of Ocular Pharmacology and Therapeutics. March 2009, 6(4): 259-269. https://doi.org/10.1089/jop.1990.6.259